Jason Victor Serinus from stereophile.com

The text, from Gary Bruestle, a speaker-positioning wizard at Definitive Audio in Seattle, left my mouth watering: “Have you heard the Apex version of a Rossini or Vivaldi yet? It’s stunningly good. Addictive, even. … I usually have a hard time relaxing and listening to music in the showroom, but the Rossini Apex DAC had me in its thrall for a few hours yesterday.”

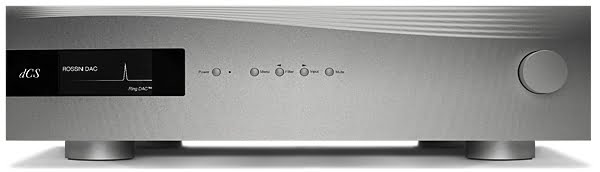

Soon thereafter, I heard from Peter McGrath, Wilson Audio’s director of sales, that he was blown away by the sound of his dCS Vivaldi Apex DAC—the flagship DAC from Data Conversion Systems (dCS) of Cambridge, England. Nor was dCS exactly shy when it proclaimed, in its March 3, 2022, press release, that the Apex version of its Ring DAC was “taking the Ring DAC’s world-leading performance to a new level.”

When Gary told me, during the phone chat that followed his text, that he believed the Apex DAC raised the Rossini’s bass response to that of the Vivaldi, I sat up in my seat. For the year the top-of-the-line Vivaldi DAC sang in my system, I reveled in its expansive soundstage, bigger, weightier, more lifelike images, and superior presentation of texture, overtones, and bass. It got me as close to the live-performance experience as I could get with medium-size floorstanders in a medium-size listening room. Might the Rossini Apex be capable of transporting me as close or closer?

My chance to find out came just a few months later, when a Rossini Apex DAC arrived for review. But before I began my audition, I sought to clarify what was going on inside the DAC’s chassis.

The Ring DAC foundation

In a YouTube video titled dCS—The New Ring DAC Apex (footnote 1), Chris Hales, dCS’s director of product development, says, “With the Ring DAC, we’re sitting somewhere in the sweet spot between absolute [voltage]precision and timing accuracy.” The choice of filter—the Ring DAC includes six for PCM, four for DSD, and one for MQA—determines where you sit in that delicate balance. In a follow-up email, Hales noted, “Whilst the filter choice can affect the listening experience, it doesn’t affect the operation of the Ring DAC itself, which remains extremely linear whichever filter is selected.”

dCS’s technical director, Andy McHarg, whose vision drove the Apex project, said that developing the new Apex Ring DAC hardware necessitated examining each component of the technology to see what could be improved. “Marginal gains mount up over time,” he says in that video (footnote 2).

The Apex edition of dCS’s Rossini and Vivaldi systems is based on a reconfigured Ring DAC circuit board with an all-new analog output stage. The challenge dCS faced as it developed the Ring DAC Apex, Hales said, was the inability of conventional test equipment to measure the Apex’s performance values with sufficient accuracy. In an email, dCS VP of Sales and Marketing John Giolas wrote, “the linearity of our DACs is so [much higher than]the industry norm, we’ve had to create our own test equipment to measure it. Conventional test equipment is wholly inadequate to measure what our DACs are capable of.

“Audio measurement systems [can]introduce noise, or distortion, or limit the frequency response, just like the thing they’re trying to measure, and there can come a point where, even if they’re not dominating what you’re measuring, these artefacts are affecting it one way or another.”

Hales explained, “A good example is when measuring harmonics, where the second harmonic inherent in the test equipment can cancel the one in the item you’re trying to measure. This can result in a measurement that is much lower than [what]it should be, one which tends to behave unexpectedly as the performance of the item under test is adjusted” (footnote 3).

Giolas corrected a few misconceptions about the proprietary Ring DAC technology found inside all dCS products. dCS began to develop the Ring DAC more than three decades ago and was the first company to offer a digital-to-analog conversion system that could process audio signals at 24-bit resolution.

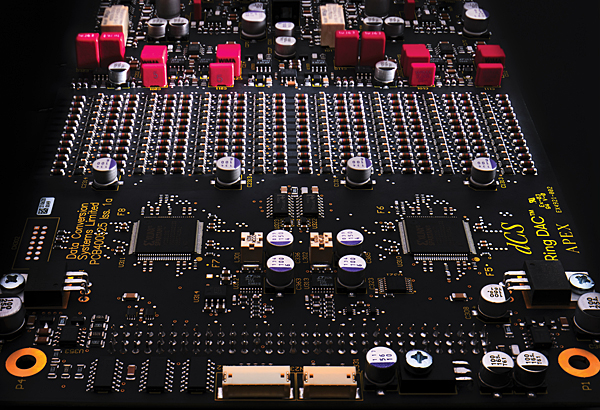

“It’s not entirely intuitive to many audiophiles that the Ring DAC is an analogue device,” Giolas wrote. “In all dCS DACs, the Ring DAC architecture is discrete and analogue. It consists of a resistor array, a voltage regulation bus, and a buffer/output gain stage that connects to the preamplifier or power amplifier (among several other things)” (footnote 4).

Hales elaborated in an email, “On the surface, the Ring DAC may look like a Ladder DAC. There is a latch and a resistor for each current source, and these current sources are fed to a summing bus. The key difference between the Ring DAC and Ladder DACs … is that the Ring DAC uses current sources of equal value. This is what is known as a ‘unitary-weighted’ or ‘thermometer coded’ DAC architecture.

“Additionally, the Ring DAC does not use the same current source(s) for the same bit every time.” (The emphasis is Hales’s.) There are 48 current sources within the Ring DAC, all of which produce an equal amount of current. The Field Programmable Gate Array (FPGA)–controlled nature of the Ring DAC allows the sources to be turned on and off in such a way that any component value errors are averaged out over time. Firing the same bit three times on the Ring DAC might give one output slightly high, the next slightly low, the next somewhere in the middle, as opposed to outputting the sample slightly high every time or slightly low every time (as seen in a Ladder DAC, for example).

“It takes a considerable amount of signal-processing power and know how to optimally operate a thermometer-coded DAC, but the benefit with this approach is that it almost entirely removes the linear distortion from the signal. (Bear in mind that the highly artificial distortion many DACs produce is very noticeable to humans and has a negative impact on perceived sound quality.)

“The Ring DAC process may be thought of as decorrelating errors. Background noise (an uncorrelated error, one which is not linked to the audio signal itself) is very prevalent in nature, whereas artificial distortion (a correlated error) is not. This results in the Ring DAC having class-leading distortion performance, particularly at lower signal levels. This means that more fine musical detail can be resolved and heard.”

Giolas took it from there: “The dCS Digital Platform (DDP) instructs the Ring DAC which resistor ‘latches’ to turn off and on via a dCS-designed software system we call the ‘mapper’. Its sophisticated quasi-randomization accomplishes this in such a way that any component value errors are averaged out, vastly improving linearity over ladder DACs and other conventional DACs.” dCS had previously addressed and improved its mapper technology in 2017, when the Rossini 2.0 upgrade provided a choice of new or legacy mapping algorithms. David Steven, managing director of dCS, noted by email, “The mapping process is vital to the performance of the DAC and is performed in programmable logic (FPGA). As we improve it, we can upgrade the performance of units in the field (eg, most recently with Bartók 2.0). The Apex hardware changes take full advantage of and build upon the high-speed mappers that were installed during the 2.0 software update to the Ring DAC.”

“The new Ring DAC Apex hardware features several modifications,” Giolas continued. “The reference supply that feeds the Ring DAC circuit board was one of the first areas that dCS engineers looked at during the research and development phase. Their investigation led them to make some significant adjustments and enhancements. The engineers also thoroughly modified and improved all subsequent stages of the Ring DAC, including the summing and filter stages. The Ring DAC output stage responsible for buffering the analogue signals generated by the Ring DAC was redesigned (footnote 5). Other changes to the Ring DAC’s hardware included replacing individual transistors on the Ring DAC circuit board with a compound pair, thereby improving symmetry and linearity, and adjusting the layout of components on the Ring DAC circuit board. The result of these various adaptations is a new, enhanced analogue board that is quieter than previous iterations and over 12dB more linear in the second harmonic.”

Setup

I placed the Rossini Apex DAC on a shelf under my reference Rossini DAC, both DACs resting on Wilson Audio Pedestals. A Stromtank S 1000 battery power source supplied power via Nordost Odin 2 cables. A Rossini Grade 1 master clock ($10,200), which I consider essential for optimal playback, paced both DACs. Settings on both units were identical: mappers (Map 1), filters (F5 for Red Book, F3 for 24/88.2 up to 24/192, F6 for higher PCM resolutions, F1DSD for DSD, and M1 for MQA), voltage output (2V, footnote 6), and upsampling format (DXD). I soon discovered that my preference for the Map 1 mapper remains unchanged with the Rossini Apex DAC; I find it richest in color saturation and contrast.

Footnote 1: See youtu.be/tZEKEYniLTo. John Giolas and Rachael Steven conducted the interviews and collaborated on the story and editing.

Footnote 2: A similar sentiment was expressed by Nuno Vitorino, director of research and development at Innuos, who wrote in an email to me and Editor Jim Austin, “It’s the sum of a very large number of small improvements on the source that end up providing a very audible benefit.”

Footnote 3: More detailed information about Apex technology can be found at dcsaudio.com/edit/apex-a-closer-look.

Footnote 4: For more on the dCS Ring DAC, see dcsaudio.com/assets/dCS-Ring-DAC-Explained.pdf.

Footnote 5: According to Hales, “The purpose of the output stage is primarily to interface us to what is unknown territory once we leave the dCS realm. We really don’t have much control over what cables people are going to connect, what external equipment people are going to connect, and these can have very different input characteristics, so it’s important to have an output stage which is capable of driving lots of current, that’s not sensitive to stability problems that these may cause. … The solution, then, is to isolate the summing stage from the outside world so that we can optimize the performance of the summing stage and drive the enormously uncertain loads that cable and amplifier combinations can present.”

Footnote 6: Listening tests conducted years ago revealed that, to my ears, Rossini’s 6V output delivers the most colorful and engaging sound. But since some preamps and integrated amplifiers that arrived for review couldn’t handle 6V, I reluctantly switched to 2V. Then, while preparing the specs for this review, I noticed that specified residual noise levels are lowest at the 6V output. With this confirmation for my 6V preference, it’s now back to 6V.